“Stand Up and Be Recognized”

September 19, 2022 | Posted in: DEI | Ken Macro | PGSF Blogs

In my last blog, I confessed about my sadness in failing to recognize my older sister throughout my life. Born four years before me, she lived on this earth for only one week. Unfortunately, I never knew her, and consequently, I think of how my life would have been enhanced were she have grown up as my older sister. All retrospect now. But it got me thinking about identifying “the forgotten” or “the unrecognized.” Given the significant movements over the past ten years to recognize people and members of marginalized groups—and to honor their histories and the sacrifice of those in past times which have become “forgotten”—it dawned on me that, as with my sister, and, through attrition, she—as with many—were not “forgotten” but rather, “unrecognized.”

I know there were a lot of commas in that last sentence, but it is a thought stream that I wish to continue. Especially concerning the printing and packaging industry, book trades, and literary circles. Because men, generally speaking, were the predominant “recognized” source for proprietors, purveyors, and provocateurs of the printed media movement that began so prevalently in early modern Europe. However, until most recently, new revelations have been made aware pertaining to the “unrecognized” women of print from the past.

In my last post, I mentioned a book entitled Women’s Labour and The History of the Book in Early Modern England (edited by Valerie Wayne, The Arden Shakespeare, 2022). In it, Wayne (2022) writes of the many women employed within the printing and book trades in early modern Europe. She writes, “The women who engaged in that work [printing and making books] range from those who raked rags from rubbish piles and begged door-to-door to receive pittance for them to those who ran printing houses and financed the production of books, sold them, wrote them, edited, owned, read and shared them” (2). According to Wayne, at least fifty-one widow publishers in London between 1540-1640 worked their businesses in some form or fashion. As it was in those days, the publishing house’s name most assuredly was identified by the husband or man of the family, even though the women (wives, daughters, sisters) could have very well actually been running the business, conducting production, and overseeing actual sales. Additionally, when the men associated with the printing and publishing business died, the widow would inherit the “shop” and—to earn wages for a living—would continue the operation in the name of their deceased husbands or newly acquired husbands.

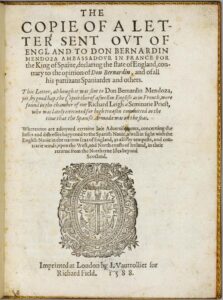

One such “unrecognized” women publisher was Jacqueline du Thuit Vautrollier Field. She was the wife of a French Hugeonot who fled France for London in the 1560s. Mr. Vautrollier was a gifted and prominent printer in London at the time. He allegedly produced over 150 titles (books) over a twenty-year span. Upon his death in 1587, his wife, Jaqueline, was prohibited from printing any books under the auspices of his business name. As such, and with much persuasion to the Stationer’s Court (in London) from Mrs. Vautrollier, she was given permission to print a leaf (one page) of the Greek New Testament (which would have been an extremely challenging and difficult project). She was also granted permission to print a book based on Luther’s work on Galatians, which was apparently 600 pages in length. Later, and because of the quality of her work, she was able to obtain further publishing opportunities, printing pamphlets for members of the Royal Court of Queen Elizabeth that were in both French and English. Strategically, she decided to take on a new husband, Mr. Richard Field. In doing so, Mr. Field, a printer himself, acquired Mr. Vautrollier’s business and operated it under his name whilst providing Mrs. Vautrollier-Field with a newly recognized status within the printing/publishing community. Mr. Field was William Shakespeare’s contemporary and the first to print Shakespeare’s work. Richard and Jacqueline went on to establish a highly respected printing and publishing operation located at “The Blackfriars by Ludgate” (formerly the Vautrolliers’ Printing House) in central London well into the late 1500s. Jaqueline du Thuit Vautrollier Field, like many other “unrecognized” women of the time, was never recorded within official logs, records from controllers, or city registers. Her identity was unknown until she was courted by Mr. Field. Able to recognize her talents, he began to imprint her name on the title page (along with his own) as the official printers of applicable works.

In this series, I hope to “recognize” the names of a few of the hard-working women who have contributed expeditiously and painstakingly to building a foundation for spreading knowledge through the printing and publishing process of times past. “Research on women in book history has moved well beyond assumptions of their invisibility to imagine equally plausible alternatives for them” (10).

Therefore, as I read this book and the many others I have acquired over the summer, it is my hope that women today, reading this blog, can appreciate the uncovering of those forgotten and invisible and—at the same time—perpetuate a continual process for bringing them forward to be affectionally and appropriately “recognized.”

Ken Macro

Professor of Graphic Communication

Cal Poly