Coming up for Air

December 23, 2022 | Posted in: Ken Macro | PGSF Blogs

Tempus Fugit. Here we are at the end of 2022. Seems like yesterday that we were learning about the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the beginnings of another nasty, hate-filled, toxic election year was in its infancy. As I sit here now, attempting to maintain continuity with regards to the last post I made (many months ago), I realize how time we invest in the many projects that stack up in our lives and, inevitably, force up to come up for air and face the morbid reality that, time, does in fact, fly by quickly.

Because I am enamored with everything “early modern England” (I have been engaged in researching sources for two writing projects that have taken me into many rabbit holes…hence the whole “come for air” metaphor I used in the paragraph above), I am taken back to that time when the Holiday season meant a more culturally in terms of religious significance (as opposed or materialistic obsessions of current times). In England, during the 16th and 17th centuries (as well as centuries past), the preparation of season required much reading (individually and communally) along with constant prayer. Such a cultural manifestation required, of course, printed matter in the form of books (prayer books, psalms, and leaflets) for the literate commoner to read and for the head of household to recite.

Because I am enamored with everything “early modern England” (I have been engaged in researching sources for two writing projects that have taken me into many rabbit holes…hence the whole “come for air” metaphor I used in the paragraph above), I am taken back to that time when the Holiday season meant a more culturally in terms of religious significance (as opposed or materialistic obsessions of current times). In England, during the 16th and 17th centuries (as well as centuries past), the preparation of season required much reading (individually and communally) along with constant prayer. Such a cultural manifestation required, of course, printed matter in the form of books (prayer books, psalms, and leaflets) for the literate commoner to read and for the head of household to recite.

Imagine the women of the household—with all their prescribed duties—busily prepping for the season, maintaining their families, employed within their chores, and, not having the time to “come up for air.” Especially, however, are the women who also worked as the wives of printers and publishers. As we discussed in the last entry, the life of Jaqueline du Thuit Vautrollier Field, she was responsible for the printing of Greek verse and some of Martin Luther’s works.

As I mentioned before, in the early modern England patriarchal culture, women were oppressed and secondary. However, as historians have uncovered (and the modern reader certainly could infer), women were vital to the family and to their husband’s work. As with the printers and publishers of this time, It is behind the scenes that these women guided, advised, counseled, and—in many cases—assisted in the production and manufacturing processes of printed matter. They composed and set type, proofed printed sheets, assisted in collation, and most assuredly aided in the decision-making process of what titles to print and publish.

One such London women printer and publisher to prominently emerge in the late 16th century was Alice Bailey Charlewood Roberts. Ms. Bailey married the printer and bookseller Mr. John Charlewood in 1589. Unfortunately, upon his death in 1593, she was left in charge of his/their business. As a widow during this time, it was imperative to have a strong financial purse in which to invest in future and prospective publishing opportunities (as well as in new type matrices and fonts), she soon, thereafter, remarried to James Roberts, a bookseller from London. It is interesting to note that upon the death of the owner of a printing business, the widow inherits the exclusive rights to reprint any previously publication from their “house” with their name imprinted as the official printer. Thus, many widows at the time ultimately remarried other printers or bookseller in which to maintain these rights and continue operations. It is suggested, through historical research, that she was a very gifted printer in that she was able to produce output much more efficiently than her previous husband or her competitors due to her ability reconfigure composition arrangements and maximize the image area of the sheet thus minimizing waste and reducing size. Because of this, she was commissioned by other prominent publisher of the time to print larger, more significant works pertaining to religious content.

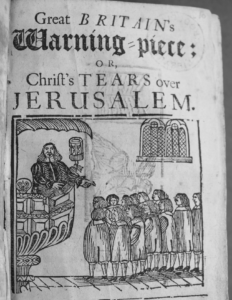

One notable book she printed was Thomas Nashe’s Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem (1592), a book previously printed by her deceased husband, but a title that remained legally in her repository. A third edition, it was a popular and successful publication for her and received great accolades within the community and her peers. Alice was distinguished as a master printer and clever publisher. Along with her new husband, James Roberts, also a successful publisher, the two contributed to the publication and printing of several important theological and popular works which proved to be quite successful.

Which brings me to the first point I made regarding the preparations for the holiday season. Alice Bailey Charlewood Roberts had ten children with her first husband Mr. Charlewood. James Roberts, marrying Mrs. Charlewood, entered a relationship that was new, unique, and challenging. I would be remiss to not mention how strong and independent Alice most assuredly was. To maintain—and grow–her deceased husband’s business, bring in a new “partner,” and, raise ten children in such times is quite remarkable. I can envision her preparing breakfast on a cold wintery English morning, scuffling her children off to school with a copy of a freshly printed leaf that had come off the press that morning. Breaking to chop some wood for the fire and preparing to wash the laundry from the days before, she opens her psalms for that day’s prayer and marks the pages in her children’s books for evening vespers. And that is just the morning tasks in her long and industrious day. I wonder if Alice Bailey Charlewood Roberts ever “came up for air.” I am sure she did, and her coming up for air was through the printed page. There is where she found refuge and sanctity. To all of you women out there today, frantically prepping for the Holidays, I hope you find sanctity too through whatever means amenable.

As the new year approaches, I raise a glass to the women printers and publishers of past who have brought refuge and sanctity to many through their unspoken, uncelebrated, and undocumented contributions to the human condition.

It is time to come up for some air.

Happy Holidays.

Cheers!

k